You Stress Me Out, and my Hypothalamus Loves It

To survive and reproduce, individuals behave in a matter befitting the acquisition and retention of lust, attraction, and attachment. Lustful behaviour intends to consolidate a sexual union with a fellow adult member of the same species. Attraction means to focus our attention on a select partner to save mating time. Lastly, attachment behaviour consolidates an affiliative connection to complete parental duties. As a result, romantic love develops as a behavioural drive, or a motivation state, to pursue an intimate relationship with a select mating partner.

Across different species, the neurological tasks of forming an attachment encompass behaviours such as approaching a potential partner, learning their identity, and investing in them while rejecting any other potential matches. To consolidate intimacy, humans must first regard another as especial and unique, while focusing their attention on aggrandizing their traits and diminishing their faults.

In his metanalysis about the neuroendocrinology of romantic love, Dr. Krishna Sidrashi claims that during the first stage of a romantic attachment, lovers experience emotional dependence, empathy, willingness to sacrifice, obsessive thinking, sexual desire, possessiveness, and mate guarding. Sidrashi also says that “there is increased ecstasy when things go well, despair when they do not and separation anxiety when apart.” Mental arousal is a common symptom of increased stress at the start of a romantic attachment.

Stress Response

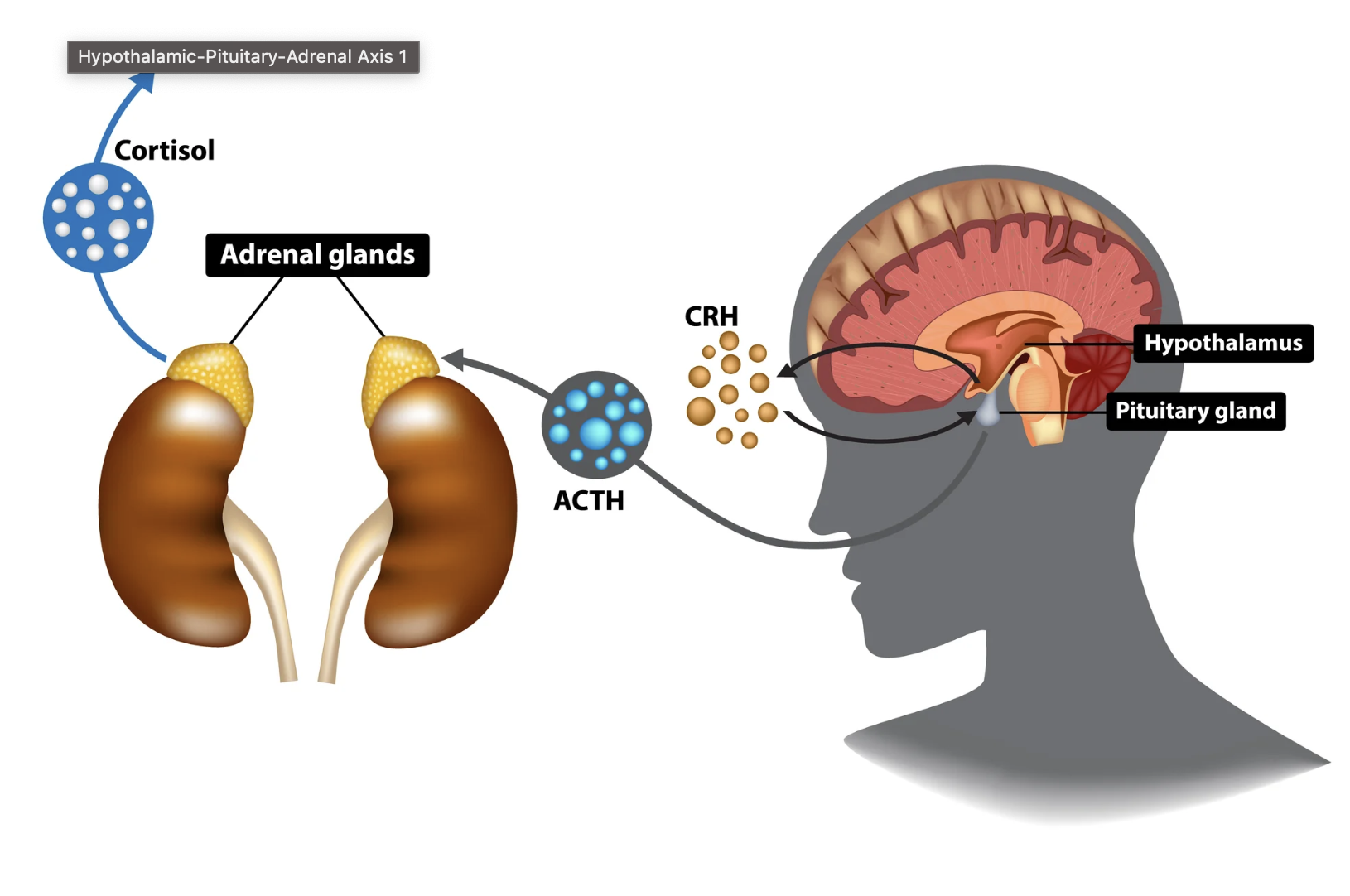

Facing feelings of infatuation foster jitters, goosebumps, and palpitations. Falling in love is exhilarating and stressful, activating the hypothalamo-pituitary adrenal axis. The hypothalamo-pituitary adrenal axis regulates stress by releasing hormones. When forming an attachment, the hypothalamus will activate the pituitary gland and regulate emotional responses, such as tenderness, joy, and lust. As the brain structure controlling primordial bodily functions and emotional responses, the hypothalamus secretes the stress hormone cortisol and the alertness hormone norepinephrine, prompting physical reactions like trembling, sweating and increased palpitations.

Source: Simply Psychology (Carter, 2017)

The hypothalamo-pituitary adrenal axis activates the brain’s stress response and reward systems.

The pituitary gland, also known as the brain’s master gland, senses the body’s physiological needs and uses nerves to communicate to other parts of the brain. By making the adrenal gland bump up perceived feelings of anxiety, the pituitary gland will activate the body’s stress response. By linking love with reward mechanisms, the attraction and sentiment hormones dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine will then exacerbate feelings of love. In the words of Sedrashi, “stress appears to be the trigger for a quest for pleasure, proximity, and closeness.”

Though stress has negative connotations, in the neuroendocrinology of attachment and affection, it reflects the body’s reaction to a wide range of positive and negative stimuli. According to Mercado and Hibel, these stimuli can range from “normative events such as a passionate kiss between new lovers to adverse circumstances such as being chased by a predator.” The interplay between the hypothalamus and the hippocampus enhances a positive stress response. As the part of the brain that regulates memory retrieval, the hippocampus interacts with the hypothalamo-pituitiary adrenal axis to connect rewarding, attachment-related emotional memories to the body’s neuroendocrine stress response. While the hippocampus activates positive neural pathways, the hypothalamus wills the body’s nerve cells and prompts hormonal secretion, in particular, of testosterone and estrogen.

Gonadal Hormones

Gonadal hormones interact with reproductive organs to increase attraction and sex drive. Testosterone supresses the hormone serotonin, decreasing aggression. Both testosterone and estrogen, the male and female sexual hormones, mediate lust and interact with the amygdala, the brain’s emotional center. The gonadal hormones will also increase territorial guarding and arousal, by affecting vasopressin and oxytocin, respectively.

At the beginning of romantic attachments, men show increased activity in brain areas related to visual stimuli, while women activate regions associated with attention, memory, and emotion. The effects of gonadal hormones coupled with the hypothalamus-mediated stress response will increase trust, attraction, and feelings of security, leading to pair bonding, the evolutionary antecedent of romantic love.

Sedrashi says that “attraction is mediated by hormones of stress and reward including dopamine, norepinephrine, cortisol and the serotinergic system.” Attraction hence reinforces feelings of reward to generate deeper attachments.

Rewards and Reinforcement

When attachment leads to feelings of reward, we call it love. Dopaminergic pathways and influxes of oxytocin –related to reward and trust, respectively– decrease negative emotions and reinforce motivation to maintain intimate romantic attachments. By decreasing emotional judgement and fear, while increasing motivation, our brain rewards and reinforces proximity to our object of affection. The hypothalamus connects to the brain’s reward system to reinforce our stress response, prompting us to seek a romantic attachment, and once a monogamous pair bond is achieved, to protect our mate and maintain intimacy.

Sources

Carter, C.S. (2017). The Oxytocin–Vasopressin Pathway in the Context of Love and Fear. National Library of Medicine, 8, 356. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2017.00356

Guy-Evans, O. (2021). Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis [Photograph]. Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/hypothalamic%E2%80%93pituitary%E2%80%93adrenal-axis.html

Insel, T. R., and Young, L. J. (2001). The Neurobiology of Attachment. Nature, 2, 129-136. https://www.nature.com/articles/35053579

Koelsch, S. (2014). Brain correlates of music-evoked emotions. Nature, 15, 170-180. https://www.nature.com/articles/nrn3666

Mercado, E., and Hibel, L.C. (2017). I love you from the bottom of my hypothalamus: The role of stress physiology in romantic pair bond formation and maintenance. National Library of Medicine, 11(2). doi: 10.1111/spc3.12298

Seshadri, K. G. (2016). The Neuroendocrinology of Love. National Library of Medicine, 20(4), 558-563. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.183479