The Prairie Vole’s Model of Monogamous Pair Bonding

Fewer than 5% of mammalian species have a monogamous social structure. Prairie voles mate for life. As affiliative social animals, prairie voles seek to foster emotional bonds with a prospective partner. After mating, prairie voles show both less interest in strangers and aggressive behaviour towards newcomers.

Mated prairie voles scurry around picking twigs to build a nest where to guard their children. The furry brown couple hug their offspring. They now share a nest, equal parenting duties, and will stay together for the rest of their lives, which will last the next two to three years. From the moment the prairie voles mated, their genetic makeup changed. Now, the couple has pair bonded.

Source: NPR (NPR Staff, 2014).

Prairie voles form monogamous pair bonds and take and egalitarian approach to raising their children.

Pair bonding occurs between members of the same species when two sexually matured adults establish enduring preference. Involving what doctors Yong, Gobrogge, Liu, and Wang call “selective contact, affiliation, and copulation with the partner over a stranger (partner preference),” pair bonded couples guard their mates and help their offspring grow.

But, what differentiates prairie voles from non-monogamous mammals? A group of scientists from the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences of Atlanta Georgia set out to answer this question.

Methodology and Testing

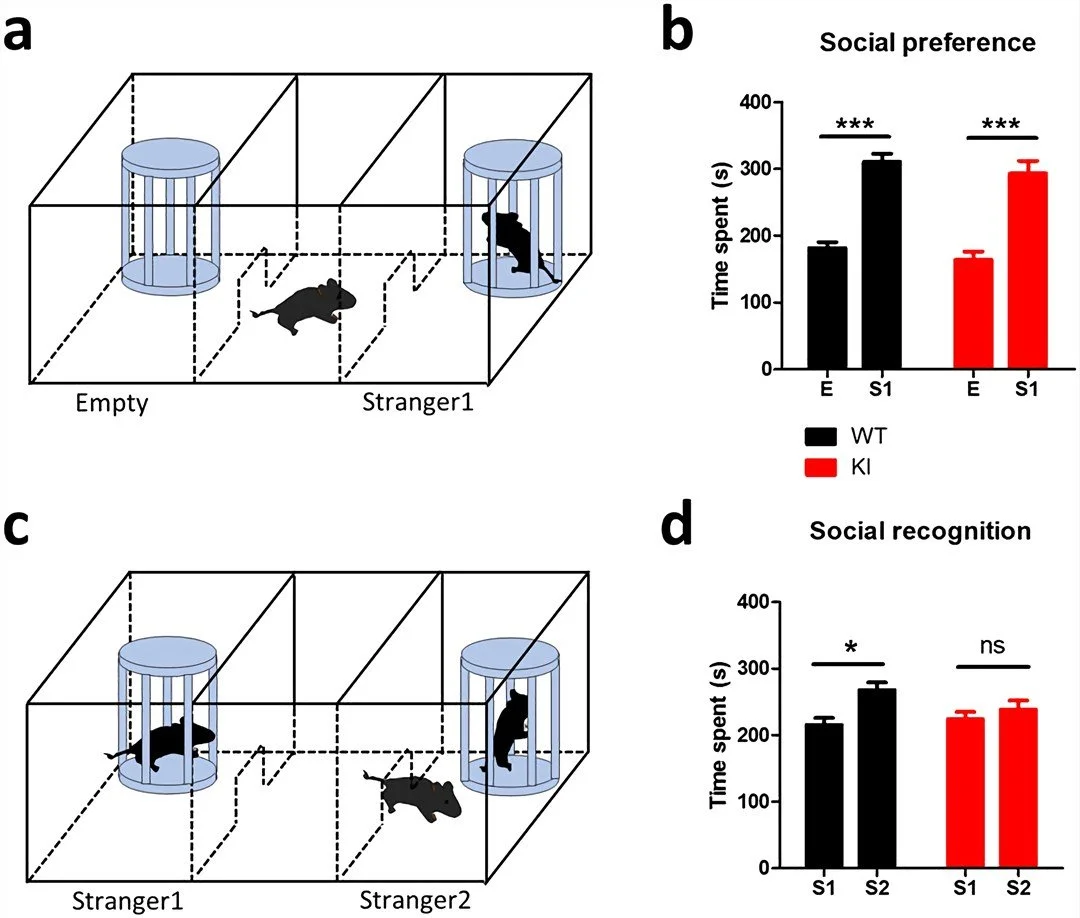

The researchers compared the behaviour and brain neurochemistry of prairie voles to that of meadow voles. They chose sexually naïve voles aged two to six months that had grown in laboratories. The scientists performed partner preference tests after the voles cohabited with a female for 24 hours. They put the male in the centre of a three-chambered box, with the female they cohabited with and a female stranger on each of the adjacent chambers. The male vole could freely move between the chambers, and scientists recorded the time spent in each cage and huddling with each female. The researchers performed the experiment twice: After the initial 24 hours and after another two weeks.

Source: Creative Biolab Therapeutics (Creative Biolab, 2014).

The three chambered box allows rodents to move freely, so researchers can gauge their behaviour in forming selective attachment bonds.

The results showed that prairie voles spent significantly more time in contact with their partner than with a stranger. In contrast, meadow voles showed no partner preferences. More than that, prairie voles behave in an affiliative way and spent a lot of time huddling, while meadow voles prefer solitude and spent little to no time huddling with each female.

Source: Nature (Lim et al., 2004)

Meadow voles prefer solitary behaviour and show less levels of vasopressin in their brains, while prairie voles show affiliate behaviour and show higher levels of vasopressin.

Photos of the voles brains showed higher levels of vasopressin in the brains of prairie voles than in those of meadow voles. While both dopamine and vasopressin regulate selective affiliation in adult male species, the photographs reflected no alterations in the dopamine levels. Prairie and meadow voles share 99% of genes, yet the difference in the shift of vasopressin within a part of the brain called the ventral palladium changed the behaviour of prairie voles towards the formation of monogamous pair bonds. Two of the researchers, Wang and Young, decided to do a follow up study about the neurobiology of pair bonding, and the significance of vasopressin.

The Neurobiology of Pair Bonding

Neurotransmitters communicate information between neurons. Dopamine modulates parental bonding, empathy and social recognition, while vasopressin prompts aggression, scent marking and courtship. Dopamine accelerates pair bonding in female voles while vasopressin accelerates pair bonding in male voles.

In particular, vasopressin promotes selective social bonding and selective aggression. After mating, male and female prairie voles get a dose of vasopressin, which makes them want to spend more time with their mate and become aggressive towards strangers. In other words, “as vasopressin increases following mating, the male not only forms a selective preference for the female but also begins to guard access to his mate.” The balance between these vasopressin-mediated, affectionate and protective types of behaviour in prairie voles prompt monogamous pair bonding. Dopamine helps reinforce the effects of vasopressin by rewarding these behaviours with feelings of pleasure.

What Humans can Learn from Prairie Voles

Pair bonding in voles evolved through evolutionary practices. Mama and papa voles adapted monogamous behaviours to effectively raise their young. The same behaviours that ensure the survival of their offspring facilitate the formation of a monogamous pair bond.

Just as with prairie voles, pair bonding has cross-cultural and evolutionary consequences for humans like us. Young and Wang, this time in partnership with Gobbroge and Liu, analyzed what humans can extrapolate from the love between rodents. They explain that high levels of intimacy decrease negative moods, while increasing immune function and cardiovascular health. Married couples live longer across demographic groups. The children of paired couples experience psychological wellbeing and positive cognitive developments due to bi-parental duties, and children with bonded parents experience lower mortality rates in impoverished communities.

The similarities of the behaviour between prairie voles and humans when mating can greatly aid the neural study of human relationships. The researchers explain it best: “Although study of the bonds formed between prairie vole pairs cannot possibly allow us to fully understand the intricacies of human relationships, they can certainly offer insights into the basic neural mechanisms underlying adult attraction and attachment.”

Sources

Creative Biolabs. (2022). Three Chamber Social Test [Photograph]. Creative Biolab Therapy. https://www.creative-biolabs.com/drug-discovery/therapeutics/three-chamber-social-test.htm

Lim, M.M., Wang, Z., Olazabal, D. E., Ren, X., Terwilliger., Young, L.J. (2004). Enhanced partner preference in a promiscuous species by manipulating the expression of a single gene. Nature 429, 754-757. https://www.nature.com/articles/nature02539#citeas

NPR Staff. (2014, February 9). Learning about love from prairie vole bonding [Photograph]. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2014/02/09/273811514/learning-about-love-from-the-lifelong-bond-of-the-prairie-vole

Young, K.A., Gobrogge, K.L., Liu, Y., & Wang, Z. (2011). The neurobiology of pair bonding: Insights from a socially monogamous rodent. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology 32(1), 53-69. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0091302210000555

Young, L. J., & Wang, Z. (2004). The neurobiology of pair bonding. Nature Neuroscience 7, 1048-1054. https://www.nature.com/articles/nn1327#citeas